EDIT: If you’d like to read Val Dunicliffe’s presentation on ‘Room’ – which gives a much more comprehensive overview of the language and thematic elements of the novel that we discussed in our sessions, then you can do so by clicking here.

Hello all – before I begin, a big apology for the delay in writing and posting this. For the past couple of weeks, I’ve been struggling to shake laryngitis and it has turned my brain to cotton wool. Hopefully, it’s now behind me!

So. Our fourth book of the course and certainly the most controversial. I have to say, when I wrote the syllabus last year (from a combination of class requests and my own favourite novels of recent years), I didn’t anticipate such a fiery reaction. It certainly did make for an interesting few hours of debate, though! With that in mind, I’d like to offer something slightly different to my previous posts – a bit of a personal perspective on Room, and the issues which dominated our discussions.

I first read the book myself back in 2010, when my then boyfriend and I decided to pick a Booker shortlister to back based on front cover alone. He read The Finkler Question and I read Room. I tore through it over the course of a long weekend in Munich. During that time, I sobbed a lot, exclaimed ‘no!’ a lot and became so antisocial that I may as well have been back in Birmingham, where I at least could have avoided being rude to the polite but chatty lady next to me on my Easy Jet flight home, who I asked to leave me alone, in order to read the last few chapters. The Finkler Question may have gone on to win the prize, but there was no question between my boyfriend and me regarding who enjoyed their book more. In short – I loved it. In fairness, this may be because I am the ideal reader of this kind of novel, for the following reasons:

- I find it very easy to suspend my disbelief (i.e. I didn’t question the escape scene at all) and to buy into (well written) characters

- I am fascinated by hypothetical questions (I love dystopian worlds, zombie apocalypses etc), so was very intrigued to imagine how a person might survive in this scenario, both physically and emotionally

- My favourite theme in any book, film or TV show is the triumph of the human spirit, which is what I saw in this novel, above all else.

By contrast, as you all know, many people in our group had a somewhat less enjoyable reading experience. Though varied, those negative responses can be somewhat condensed into three main issues:

- The book is badly written, and can not be classed as ‘good literature’

- Making money from a real life tragedy – where the victim is still living, i.e. Elisabeth Fritzl – is exploitative

- It is morally objectionable to appropriate the voice of a victim whose suffering is beyond the realms of the writer’s own experience.

In the spirit of playing Devil’s Advocate, I’d like to offer a response to each of those issues in turn.

- Room does not constitute good literature.

Well, this is an opinion, of course. There is no official definition of ‘good literature’, as Rick Gekoski so ardently reminds us in this opinion piece from The Guardian, though we often use the phrase with confidence. But for the sake of this blog post, I googled it. The first result I was given – from the good people at Reference.com – was this:

“Great literature is a story that encapsulates the time period in which it was written, while maintaining universal themes regarding human existence. Great literature is able to do this through artistic prose that is accessible to the reader while representative of the character.”

This quote more or less sums up our group’s definition of good literature, and is frustrating in its subjectivity. Personally, Room ticks all the boxes. However, for many of our group, Donoghue’s prose was not ‘artistic’ (Jack’s limited point of view was at times frustratingly simple and at times jarringly complex), and lacked depth in terms of ‘universal themes’. So, although it was interesting to discuss our differing reactions to the novel, the question of whether it is ‘good literature’ is arguably moot, since none of us are capable of empirically proving our case.

2. Room is exploiting tragedy for cash.

This is a difficult one to argue against. It is, reportedly, true that the novel made Donoghue a lot of money, and that she had written the screenplay before the novel was published, anticipating film offers. What’s more, the novel got her onto the Booker shortlist and the screenplay got her an Oscar nomination. In Donoghue’s own words in this interview with The Telegraph: “considering it’s such a dark subject, it’s brought nothing but happiness to me.”

But Donoghue herself is keen to dismiss the accusations of exploitation. In this article from The Guardian, Donoghue denies that she was ‘inspired’ by Fritzl:

“I’d say it was triggered by it. The newspaper reports of Felix Fritzl [Elisabeth’s son], aged five, emerging into a world he didn’t know about, put the idea into my head. That notion of the wide-eyed child emerging into the world like a Martian coming to Earth: it seized me.”

Ultimately, I’d argue that this is another issue that comes down to opinion, and thus another moot point. The lucrative nature of tragic real life storytelling (across all art forms) is undeniable: consider Birdsong, War Horse, Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan, The Boy In The Striped Pyjamas, Inglourious Basterds, We Need To Talk About Kevin, 12 Years a Slave, Django Unchained, The Color Purple, JFK, United 93, Flight 93, World Trade Center, Hurt Locker, Homeland, Mandela: Long Walk To Freedom, Suffragette, The Accused, The Collector, I Am Daniel Blake to name just a few.Whether this constitutes exploitation is up for debate (and indeed was in our sessions). These ideas are perhaps best discussed in ‘negative response no.3’…

3. Appropriating someone else’s suffering is morally wrong.

This issue was perhaps the most contentious in our discussion. In our second session, I mentioned Lionel Shriver (author of We Need To Talk About Kevin) giving her two cents on the idea of cultural appropriation, as her keynote speech at the Brisbane Writer’s Festival, and the response of someone who was so enraged by the speech that she stormed out half way through. Both are worth reading. On a personal note, I find both sides compelling, but I’d like to offer my own thoughts on appropriation too.

I do not believe there should be any limit to the voices that a writer (or indeed any artist) may adopt per se. To say so, in my opinion, would be to dismiss the very nature of creativity, which is to imagine, to empathise, to build bridges between worlds. For me, the problem arises when appropriation is used lazily, and reinforces stereotypes (intentionally or not) which limit the scope of that voice. For example, I do not find Shriver’s We Need To Talk About Kevin morally objectionable, because the narrator’s perspective is balanced, believable and – most of all – compassionate. I do find Mickey Rooney’s portrayal of a Japanese neighbour in Breakfast at Tiffany’s morally objectionable, since it perpetuates ugly, xenophobic stereotypes of the time.

The point I am making here is that it is not appropriation of suffering – or whether the victims of said suffering are still alive – that is the problem. The problem is whether the appropriation expands or limits the scope of that sufferer’s voice.

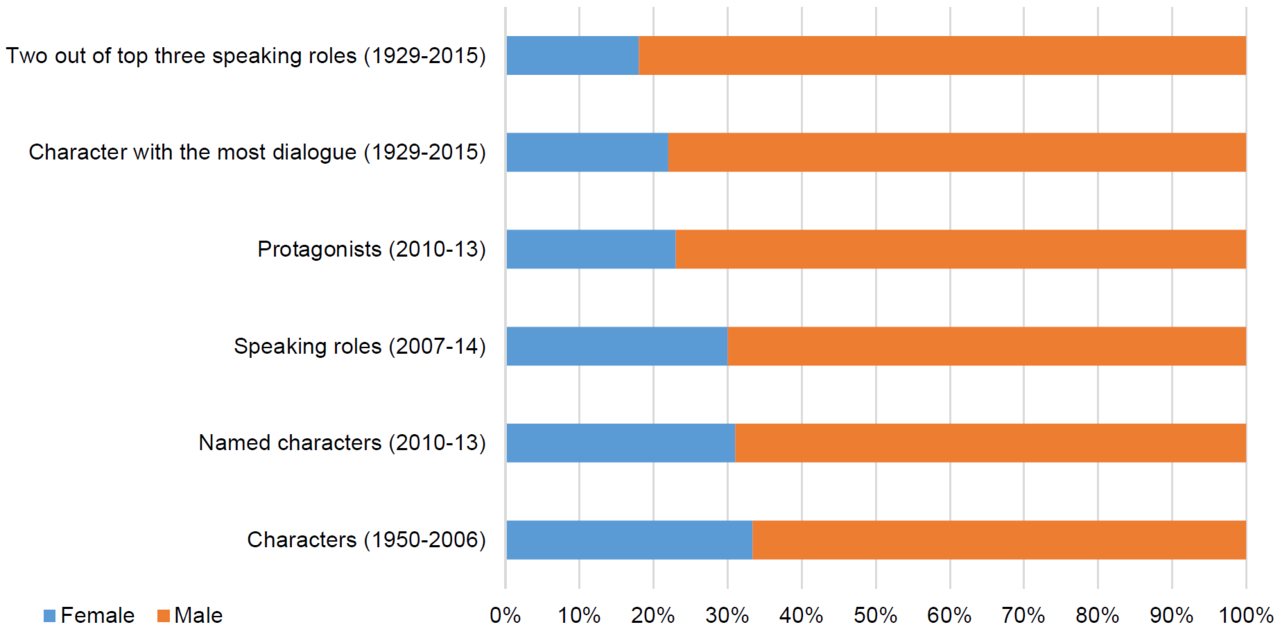

Art has the power to do both. In terms of an art form limiting the scope of a voice, consider Hollywood cinema (a male dominated industry at every level), where female leads are almost always young, white and thin. Furthermore, they are invariably compliant, emotionally vulnerable and talk about nothing but men, if required to talk at all. If you don’t believe me, look at this table (an aggregate of four comprehensive studies into film), and read about the Bechdel test.

As a consequence of Hollywood (where 75% of production crews are male) appropriating and limiting the female voice, any woman that attempts to model herself on the ‘aspirational’ female characters on the silver screen is likely to face a lifelong sense of inadequacy, particularly if she is doesn’t fit the ‘young, white, thin’ criteria.

The problem is present in literature too, as articulated by Virginia Woolf in A Room Of One’s Own:

“All these relationships between women, I thought, rapidly recalling the splendid gallery of fictitious women, are too simple. […] And I tried to remember any case in the course of my reading where two women are represented as friends. […] They are now and then mothers and daughters. But almost without exception they are shown in their relation to men. It was strange to think that all the great women of fiction were, until Jane Austen’s day, not only seen by the other sex, but seen only in relation to the other sex. And how small a part of a woman’s life is that?”

This may all seem tangential, but my point is this: appropriating a voice and then limiting it is, in my opinion, wrong.

By the same token, appropriating a voice in order to expand its reach or to expand the empathy of one’s audience is, in my opinion, virtuous. For instance, while teaching in Vietnam, I read The Boy In The Striped Pyjamas to my Year 8 students. To my amazement, they hadn’t heard of the Holocaust. Through the course of the unit, I aimed to communicate to them the atrocities of war from a human perspective. They wrote letters from the perspective of the main character (a young Nazi) to his best friend (a Jewish boy), and in appropriating his voice, they developed compassion and understanding. Several of them cried at the end of the novel, and told me how glad they were that things like that don’t happen anymore (!). For what it’s worth, I don’t think the novel is particularly well written, nor is the plot particularly plausible. However I do consider it to be a virtuous example of appropriating suffering, having witnessed the profound impact it had on my students, in terms of expanding their empathy by giving voice to a form of suffering that they had no knowledge or experience of.

With that in mind, I believe that the suffering appropriated by Donoghue in Room is morally virtuous. Donoghue gives a voice to a kind of victim that is often confined to salacious tabloid articles. Such articles invariably concentrate on the depravity of the victim’s captor and the visceral horror of their ordeals. By contrast, Donoghue expands our empathy and understanding for such victims, by creating characters that are realistic, resilient and – perhaps most of all – human. Ma and Jack are ultimately defined not by their suffering but by their power to overcome it, and if that’s not a ‘universal theme regarding human existence’ then I don’t know what is.

I’d like to end by referencing the Netflix sitcom Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. Kimmy Schmidt – written by uber-feminist Tina Fey – (bravely? bizarrely? offensively?) deals with the life of a woman who has just been rescued from a 15 year stint trapped in an underground bunker, where she was psychologically and sexually abused by a cult leader. Even I was sceptical of this one, but by the end of episode one, I was in agreement with the critics: Kimmy Schmidt is the show feminists have been waiting for. Tonally, it’s worlds apart from Room but they share a common feminist angle: they examine a world where women are victims, and they give them a powerful voice.

Further Reading / Miscellaneous Ideas

- Sorry that this article hasn’t focused at all on the language/themes of the novel, and sorry if any of the above opinions seem accusatory. My intention is only to present my opinion, as a counterpoint to the prevailing ideas of our discussions.

- You may be interested to read about Kevin Brooks’ Bunker Diary – a young adult novel which won the 2014 Carnegie Medal – elicited outrage from adults, on account of its subject matter (similar to Room) and relentlessly bleak plot (less of a happy ending than Room).

- You may remember me mentioning Freud’s theory of sublimation, and how Donoghue seems to explore the idea through Jack’s struggle to let go of his dependence on Ma (i.e. through nursing). Here’s the link to the video I couldn’t show in our class.

- From that same video series, here’s an explanation of Plato’s allegory of ‘The Cave’, which Donoghue often talks about as a model for her novel.

- Click here to download our session handout

- COMING SOON: I will upload Henny’s presentation about Room as soon as I can figure out how to scan it in to my computer!

- I do hope you’ve found this interesting – please feel free to add your own opinions in the comment section!

Best wishes,

Emily x

Wow Emily what an interesting and thought provoking summary .

I look forward to reading Henny’s introduction too.

I was sorry to have missed such a lively discussion. Isn’t that just what our class should be about?

So look forward to seeing you all again on Tues

Sue

LikeLike

Yes, Emily I agree with Rick Gekoski on ‘what makes a great book’ – and a lot of these things, complexity of theme, depth and quality of feeling, memorableness, …can be found in Room. As you list, many very difficult and dark subjects are covered in great novels, and this particular subject has unfortunately been in the headlines very often in recent times. Whether this is because as women gain a stronger place in society, feeble or psychologically damaged men have a greater urge to dominate or because they have more resources to be able to plan, kidnap, trap or incarcerate someone else for their own enjoyment, who knows?

Although Elizabeth Fritzl has been mentioned in reviews, the circumstances described in the book better fit the imprisonment of Jaycee Dugard, who was kidnapped on the way to school and kept in a storage shed in a garden in California for 18 years. She was also found by the police in a similar way. Dugard has since written two books about her imprisonment, so she is not repelled by publicity about what happened to her – although of course she does still keep her anonymity.

The wonderful thing about the book is the way in which the Mother brings up the little boy Jack, in a world of tremendous imagination, creativity, education, activity and most of all with absolute love. Never allowing him to know that they are trapped in a steel box, controlled by a dangerous psycho, but all the time being aware that the older Jack gets the more dangerous is his position – so she must work on a plot to get them out.

It is a valuable book about a tremendously brave and resourceful young woman.

LikeLike

Hi Ann,

Thanks for this – I just read into Jaycee Dugard a little bit and you’re right: her story parallels Room even more than Elisabeth Fritzls.

And I agree with all of your comments about the strengths of the book: as we were discussing Italian cinema today, I thought of La Vita E Bella, which uses the historical backdrop of the Holocaust to say something similar to Room about the triumph of human spirit in the most dire circumstances.

LikeLike